What can you do in 32 minutes? The answer might be mowing the lawn, cooking a plate of pasta, or even watching two episodes of a sitcom if you skip the intros and ads. But if you’re one of the 600 workers at the Rolls-Royce factory in Goodwood, England, you’ll know exactly what you can accomplish in this time frame.

Thirty-two minutes is the allotted time for each station on the production line, from the paint shop to the final checks before delivery, at the Rolls-Royce factory. Regardless of your team’s specific task, meeting the strict deadline of 14 cycles per shift is crucial to avoid costly delays in delivering the cars to VIP customers (who may have ordered them as far back as two years ago) at an average cost of £440,000 each.

Six hundred people are working on the Rolls-Royce production line at the Goodwood factory.

In reality, each station is only allocated 28 minutes, with the remaining 4 minutes serving as a buffer for unexpected situations like a stuck bolt or a twisted wire. Every day, across two shifts, the line at Goodwood must produce 28 cars, from painting, assembly, interior finishing, quality checks, test drives, and preparation for shipping.

The figure of 28 cars per day is minuscule compared to the output of factories like Toyota or Nissan, or even Bentley. But remember, Rolls-Royce doesn’t make “ordinary cars.” Each vehicle here is a “commissioned work of art,” designed according to the distinct personality of its future owner and subjected to a rigorous post-production quality inspection that would make even NASA squirm.

The Rolls-Royce Spectre, with its dual-motor electric powertrain and 102 kWh lithium-ion battery pack, must also smoothly, logically, and with as few concessions as possible, fit into this strict and ancient framework. However, the Rolls-Royce factory doesn’t use automated robots like other manufacturers. Instead, most of the work is still done by hand, making it far more complex to introduce a new electric model to the production line.

The Rolls-Royce Spectre replaces the massive V12 engine with an equally imposing 102 kWh battery pack.

This is where Greg Denton comes in. As the Director of Production at Rolls-Royce, he shoulders the challenging responsibility of ensuring that the entire system runs as smoothly as the priceless Audemars Piguet watch integrated into the dashboard of their £30 million drophead car.

Mr. Denton (right) explains how the first Rolls-Royce Spectre was produced.

Mr. Denton joined the Goodwood factory in 2019. Prior to that, he worked at the Mini plant in Oxford, where he held various positions since 1992, starting at the Pressed Steel Fisher plant that stamped out body panels for Rolls-Royce. “It feels like a full-circle journey,” he says about returning to the luxury car brand.

“I’ve witnessed the entire evolution of car manufacturing in the UK,” he tells Autocar, recalling the journey of the Oxford plant from its British Leyland days to BMW ownership and three generations of the Mini revival. However, what’s most relevant to his current role at Goodwood are the final, formative months at Mini, when the plant was in the process of integrating a revolutionary and technically alien model into commercial production.

“Just before I left Oxford, we had just finished integrating the electric car into the production line,” he says, referring to the launch of the first-generation Mini Electric in early 2020. The Mini Electric, with its familiar silhouette and front-wheel-drive layout, could easily be mistaken for a petrol-powered Cooper, yet underneath, it’s entirely different. Thus, adjusting the Oxford production line to accommodate it required a lot of effort.

So, Mr. Denton is clearly the right man for the task of integrating the electric Spectre into the Goodwood production line. “It’s all about flexibility,” he says when asked about the key to efficiently producing two distinct powertrains simultaneously. “Building a system that can produce both internal combustion engines and electric motors is key. You can see that when you walk around the factory: we are genuinely totally flexible, and that’s definitely the right way to go.”

The first Rolls-Royce Spectre being assembled.

From an observation position in the corridor above the start of the production line, one can understand what Mr. Denton means. Fresh from the paint shop, a gleaming new Spectre quickly enters Station 1 as a Rolls-Royce Cullinan exits. Before that, the Cullinan had replaced a Ghost. Meanwhile, the Ghost is now tailing a larger Phantom into Station 3. And so it goes, the entire process seemingly complex and dizzying.

Two hundred and thirty workers in a shift move around each other in a graceful, choreographed dance, exuding a sense of relaxed confidence that’s almost hard to believe, especially considering the tight deadlines looming ahead.

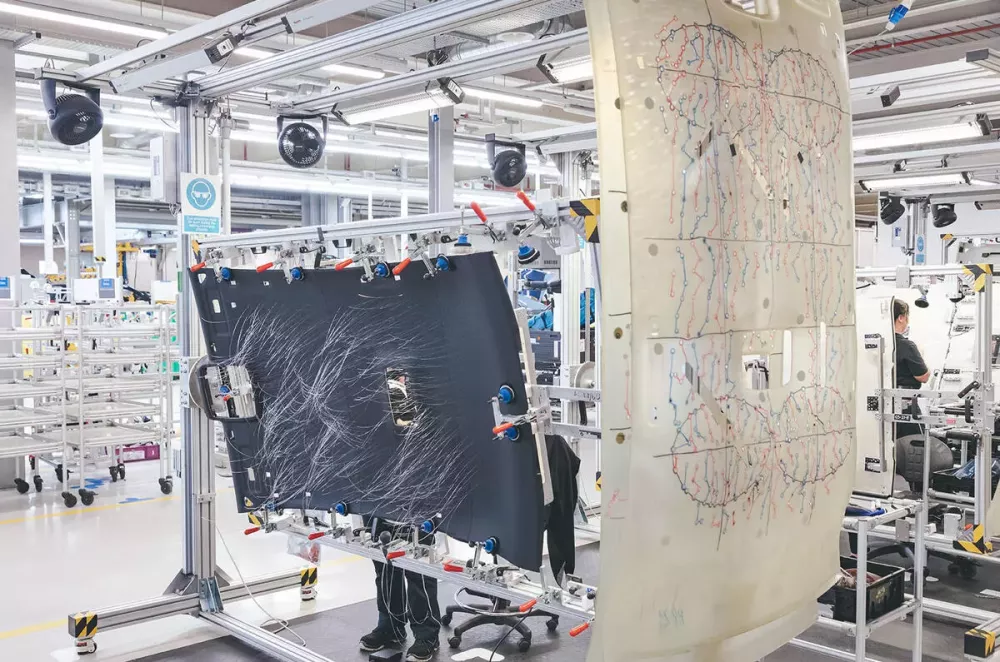

Door panels, headliners, and dashboards are neatly arranged in undulating rows alongside the production line. Each component is destined for a specific car and is painted in the customer’s chosen color combination or adorned with personalized motifs.

The starry headliner remains a popular option.

Small electric vehicles whiz up and down the line, supplying parts to each station, ensuring they’re always ready for the next car. Parts are delivered precisely every 32 minutes from the on-site parts warehouse.

“This is a time-critical system in the true sense,” Mr. Denton explains, once again emphasizing the importance of avoiding any hiccups in the startup of production for Rolls-Royce’s first electric car.

According to Mr. Denton, there’s a key reason why all four Rolls-Royce models are assembled in sequence on the same line instead of setting up a separate production system for the Spectre. “If demand for any of those products changes, we can adapt,” he explains. “If you have a separate plant and plan to produce, say, 10 cars a day, and demand doesn’t reach that figure, what do you do with the excess capacity? Conversely, if demand increases and you’re limited to 10 cars, you can’t scale up.”

Fortunately, all current Rolls-Royce models, including the Spectre, are developed on a shared platform called the “Architecture of Luxury.” This means that the cars will share many fixed points and dimensions, all contributing to the brand’s relentless pursuit of flexibility.

After reaching about 90% completion, with the headliner, dashboard, interior, trim, doors, and windshield installed, the car is rotated 90 degrees to return to the main line. “This is probably the area that required the most adjustment to accommodate electrification,” Mr. Denton explains.

Next, each car is lifted by a massive overhead gantry and moved through the final stages before the wheels and powertrain—the components that enable the car to move under its power—are installed.

The charging port of the Rolls-Royce Spectre is assembled at the end of the production line.

“We had to completely change the way we lift the car, because we had to leave space for the battery pack,” Mr. Denton says. The additional weight of the battery pack means the Spectre can’t return to the gantry once the powertrain is installed.

The solution was to extend the line with three additional stations and keep the car on them throughout this phase, installing the wheels earlier in the process to enable the car’s first roll.

The finished cars undergo rigorous quality checks.

“This was a fundamental change,” Mr. Denton says. “Two years ago, we had a two-week summer break, and during that time, this entire line was completely rebuilt.” One hundred and fifty contractors were involved in restructuring this specific area, marking the most fundamental change in the production process since the Goodwood factory started operations in 2003.

Overall, what’s surprising is how little Rolls-Royce had to change to prepare for the electric era. “In some areas of the line, the process is a little more complex,” Mr. Denton admits. “But there are also areas that are exactly the same, and in some cases, even simpler.”

He cites the powertrain assembly area as an example: “With internal combustion engines, you have to install the engine onto the axle, then the gearbox, but with electric cars, those steps are gone, so there are some stations with significantly reduced workloads.”

Some areas have been cleverly repurposed for the Spectre, such as the engine installation station now handling batteries, and the team responsible for the fuel filler neck now in charge of the charging port. Those who once installed fuel lines are now tasked with threading the Spectre’s high-voltage battery cables through the chassis.

Workers who once installed fuel lines are now threading the Spectre’s high-voltage battery cables through the chassis.

“Actually, most things are very, very similar, and I think that’s what surprised us the most,” Mr. Denton concludes. “A pleasant surprise that it’s not that different.”

In other words, while the transition to pure electric cars may be the most revolutionary step in Rolls-Royce’s 120-year history, the brand itself… hasn’t changed much.

“The less, the better,” Mr. Denton smiles in agreement. Just as they’ve always planned.